Graphite is a professional 2D graphics editor for photo editing, image manipulation, graphic design, illustration, data visualization, batch processing, and technical art. It is designed to run on a variety of machines, from mobile hardware like iPads or web browsers on midrange laptops up to beefy workstations with dozens of CPU cores and multiple GPUs.

To provide a responsive user experience, its architecture is made to support the use of distributed computation to make up for deficiencies in local compute power. Resulting productivity benefits will scale for users on hardware ranging from low-end mobile devices up to high-end workstations because documents and use cases can grow to great complexity.

This article explores the current thinking about the problems and potential engineering solutions involved in Graphite and Graphene for building a high-performance distributed computing runtime environment. We are only just embarking on the graph engine implementation, meaning this post describes theoretical approaches to theoretical challenges. The aim is to shed light on what will need to be built and what we currently believe is the trajectory for this work. We hope this post prompts discussions that evolve the concepts and approaches described herein. If this topic sounds interesting and you have feedback, please get in touch.

Node-based editing

A core feature is Graphite's reliance on procedural content generation using a node graph engine called Graphene. In traditional editors like Photoshop and Gimp, certain operations like "blur the image" modify the image pixels permanently, destroying the original (unblurred) image information.

Graphite is a nondestructive editor. Its approach is to represent the "blur" operation as a step in the creation process. All editing steps made by the user are encoded as operations, such as: import or resize an image, draw with a paintbrush, select an area with a certain color, combine two geometric shapes, etc.

Operations are functions that process information and are called nodes. For example, the "Blur" node takes an image and a strength value and outputs a blurred version of the image. On the advanced end, machine learning-powered nodes may do things like image synthesis or style transfer. Many nodes perform a wide variety of image editing operations and these are connected together into a directed acyclic graph where the final output is the pixels drawn to the screen or saved to an image file.

Many nodes process raster image data, but others work on data types like vector shapes, numbers, strings, colors, and large data tables (like imports from a spreadsheet, database, or CSV file). Some nodes perform visual operations like blur while others modify data, like performing regex matching on strings or sorting tables of information. For example, a CSV file might be imported, cleaned up, processed, then fed into the visual nodes which render it in the form of a chart.

Different nodes may take microseconds, milliseconds, seconds, or occasionally even minutes to run. Most should not take more than a few seconds, and those which take appreciable time should run infrequently. During normal operations, hundreds of milliseconds should be the worst case for ordinary nodes that run frequently. Caching is used heavily to minimize the need for recomputation.

Node authorship

The nodes that process the node graph data can be computationally expensive. The goal is for the editor to ordinarily run and render (mostly) in real-time in order to be interactive. Because operations are arranged in a directed acyclic graph rather than a sequential list, there is opportunity to run many stages of the computation and rendering in parallel.

Nodes are implemented by us as part of a built-in library, and by some users who may choose to write code using a built-in development environment. Nodes can be written in Rust to target the CPU with the Rust compilation toolchain (made conveniently accessible for users). The same CPU Rust code can be reused (with modifications where necessary) for authoring GPU compute shaders via the rust-gpu compiler. This makes it easier to maintain both versions without using separate code files and even languages between targets.

Sandboxing

For security and portability, user-authored nodes are compiled into WebAssembly (WASM) modules and run in a sandbox. Built-in nodes provided with Graphite run natively to avoid the nominal performance penalty of the sandbox. When the entire editor is running in a web browser, all nodes use the browser's WASM executor. When running in a distributed compute cluster on cloud machines, the infrastructure provider may be able to offer sandboxing to sufficiently address the security concerns of running untrusted code natively.

The Graphene distributed runtime

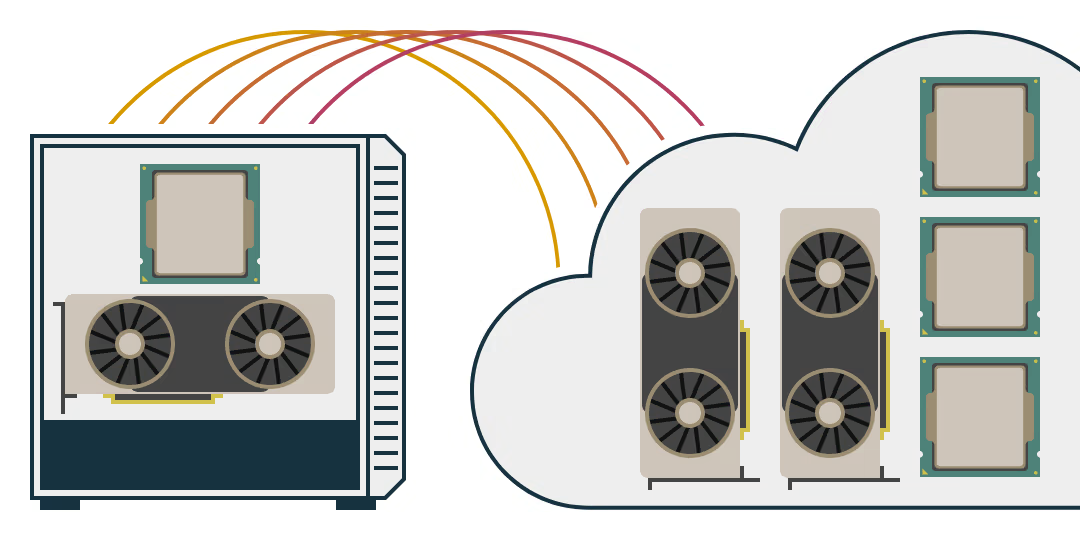

In the product architecture, Graphene is a distributed runtime environment for quickly processing data in the node graph by utilizing a pool of CPU and GPU compute resources available on local and networked machines. Jobs are run where latency, speed, and bandwidth availability will be most likely to provide a responsive user experience.

Scheduler

If users are running offline, their CPU threads and GPU (or multiple GPUs) are assigned jobs by the local Graphene scheduler. If running online, some jobs are performed locally while others are run in the cloud, an on-prem compute cluster, or just a spare computer on the same network. The schedulers generally prioritize keeping quicker, latency-sensitive jobs local to the client machine or LAN while allowing slower, compute-intensive jobs to usually run on the cloud.

Each cluster in a locality—such as the local machine, an on-prem render farm, and the cloud data center—runs a scheduler that commands the available compute resources. The multiple schedulers in different localities must cooperatively plan the high-level allocation of resources in their respective domains while avoiding excessive chatter over the network about the minutiae of each job invocation.

Cache manager

Working together with the scheduler, the Graphene cache manager stores intermediate node evaluation results and intelligently evicts them when space is limited. If the user changes the node graph, it can reuse the upstream cached data but will need to recompute downstream nodes where the data changed. Memoization can be used to avoid recomputation when an input to a node is the same as received in the past, and that result is available in the cache.

Progressive enhancement

The scheduler and cache manager work in lockstep to utilize available compute and cache storage resources on the local machine or cluster in order to minimize latency for the user. Immediate feedback is needed when, for example, drawing with a paintbrush tool.

Sometimes, nodes can be run with quality flags. Many nodes (like the paintbrush rasterizer) are implemented using several different algorithms that produce different results trading off speed for quality. This means it runs once with a quick and ugly result, then runs again later to render a higher quality version, and potentially several times subsequently to improve the visual fidelity when the scheduler has spare compute resources and time. Anti-aliasing, for example, will usually pop in to replace aliased renders after a few seconds of waiting.

Batched execution

It is important to reduce the overhead between executions. Sometimes, Graphene will predict, or observe during runtime, the frequent execution of code paths (or rather, node paths) with significant sequential (not parallel) execution steps. These are good candidates for optimization by reducing the overhead between each execution.

In these cases, Graphene will batch multiple sequentially-run nodes by recompiling them such that they are inlined as one execution unit. This can happen for both CPU-based programs and GPU-based compute shaders. This is conceptually similar to how just-in-time (JIT) compilers can predict, or observe at runtime, frequently-run code paths in order to apply compiler optimizations where they are most impactful.

Data locality

When dealing with sequential chains of nodes, if they haven't already been recompiled as a batched execution unit, the Graphene scheduler may also frequently prioritize grouping together a set of related nodes to be run together on the same machine for memory and cache locality.

Sequential nodes allocated to the same physical hardware can avoid the overhead of copying data over the internet, or between machines in the cluster, or between RAM and VRAM, or from RAM to the CPU cache.

Graphene should recognize when a certain intermediate result already lives in RAM or VRAM and prioritize using that CPU or GPU to compute the tasks which rely on that data. But when that's not possible, we need a fast architecture to transfer data between machines. For GPUs, it might be possible to use a DMA (Direct Memory Access) strategy like Microsoft's new DirectStorage API for DirectX and transfer data into or out of VRAM straight to SSDs or networked file systems. Efficiently transferring the final result, and maybe occasionally intermediate cache results, between networks (like the cloud and client) with latency and bandwidth considerations is also important.

Conclusion

Presently, we are experimenting with CPU and GPU node composition for the beginnings of the Graphene visual programming language. Most of what was described in this post will likely evolve as we get further into the implementation stage and when we learn more from experts in the fields of computer science that Graphene overlaps with.

If you have a background or interest in programming language design, functional programming, ECS and data-oriented design, scheduling, distributed computing, general-purpose GPU compute (GPGPU), or high-performance computing (HPC), we'd love to have your ideas steer our work. Or better yet, join the team to make this dream a reality. We discuss most of our architecture and designs on our Discord server through text and sometimes voice. Please come say hi!